Complex Azerbaijan Politics – a travel blog

I’ve had Azerbaijan on the brain since doing the research for Chapter Five of Languages in the World. How History, Culture and Politics Shape Language with Phillip M. Carter (Wiley-Blackwell, 2016). So I had to come here … and then became aware of the complexity of Azerbaijan politics.

Chapter Five is entitled “The Development of Writing in the Litmus of Religion and Politics.” In the Final Note we describe how the relatively small country of Azerbaijan has experienced four alphabet changes in the last 100 years.

Call it alphabetic whiplash.

So, how the heck did that happen?

The answer is: Religion and Politics. Azerbaijan politics is particularly complex.

#1) The Azeri are Muslim, so the writing system was Arabic when they converted to Islam, beginning in the seventh century.

#2) When Azerbaijan was incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1920, the Bolsheviks changed the Azerbaijan alphabet to Latin in order to disrupt the association between the Arabic alphabet and religion.

#3) When Stalin came to power in the 1930s, he wanted all languages in the Soviet Union to be written in Cyrillic. So Azerbaijani was transliterated from Latin into Cyrillic.

#4) After the collapse of the Soviet Union and Azerbaijan independence in 1991, the people in charge decided to transliterate Azerbaijani back into the Latin alphabet.

Given this history, naturally I had to go to Azerbaijan .

Alphabet changes aren’t the only disruptions, as it turns out. Azerbaijan’s borders have been equally disrupted.

Take a good look at the map of Azerbaijan:

You will notice a green part in the southwest floating apart from the rest of the country. This is Naxçivan, and it is called an autonomous republic. It is isolated from the rest of Azerbaijan by a sliver of Armenia extending south to Iran. The borders are as complex as Azerbaijan politics.

The only way an Azerbaijani can get from the main part of the country to Naxçivan is by plane. No cars, no buses, not even a boat by river.

The salmon-colored area inside the green area is called an autonomous oblast. It is (somewhat?) controlled by Armenia.

The beginning of an Armenian corridor between the two parts of Azerbaijan began in 1813.

Ask my guide, Basrad, who the culprit really is, and I’ll give you one guess. Yes, it’s Russia. Stalin, apparently, gave Armenia the go-ahead for the final land grab in the 1930s that completely separated the two parts of Azerbaijan.

It’s hard to believe, but what is happening today in Syria is the equivalent of what the Azerbaijani suffered when they were bombed and massacred by Armenians (and Russians) during and after the break-up of the Soviet Union 1989 – 1994.

In Baku, what was once called Highland Park is now Martyr’s Avenue. Here are two views of it:

It is an impressive memorial for those who died in the worst of it, in 1990. Complex Azerbaijan politics, indeed.

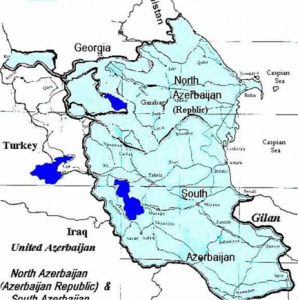

Speaking of borders, there’s the tricky bit with Iran, which is to the south of Azerbaijan. In the National History Museum, the map of Azerbaijan looks like this:

As far as the world is concerned, North Azerbaijan is Azerbaijan. South Azerbaijan, whose central city is Tabriz, is in present-day Iran. The population there is Azeri and they speak Azerbaijan, a Turkic language, which is different than the Farsi/Persian, an Indo-European language, spoken in Iran.

Note, furthermore, that on the map, above, there is no Armenian corridor separating the two parts of present-day Azerbaijan.

A country can hope.

There are Azeris today who long for a united Azeri population, just as there are Romanians who long for România mare – that is, ‘big Romania’, which includes Moldova and a part of Bulgaria where people speak Romanian – and Poles who still think of four great Polish cities, only two of which – Warsaw and Krakow – are in present-day Poland. The other two are: Vilnius in present-day Lithuania and L’viv in present-day Ukraine. Unfortunately, in L’viv the Polish language has been wiped out of the local culture.

Back to Azerbaijan. My guide, Basrad, told me about a radio station called Günaz, which regularly broadcasts programs favoring the independence of South Azerbaijan.

Linguistic note: gün means ‘south,’ so gün + az(erbaijan) is the rationale for the name.

Question: Where is this radio station?

Answer: Chicago, Illinois – my hometown.

Globalization is a strange phenomenon.

Just to underscore how complicated borders can get in this region, it turns out Azerbaijan shares a border with Turkey. To find it, locate the city Heydarabad on the north tip of the autonomous region of Naxçivan. There’s a sliver of land to the northwest which is not labeled Armenia or Iran … and that’s Turkey.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the one who united modern Turkey after the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, made some kind of deal with the powers-that-be to get this border.

His idea was no different than the Azeris, the Romanians and the Poles who want national borders to line up with (historic and) linguistic borders. Atatürk envisioned a world where Turkic-speaking peoples would be united.

He got 11 kilometers.

Better than nothing. As I’ve said, the Azerbaijan borders are as complex as Azerbaijan politics.

See also: All My Asia Blogs

Categorised in: Adventure, Central Asia, Thoughts

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment